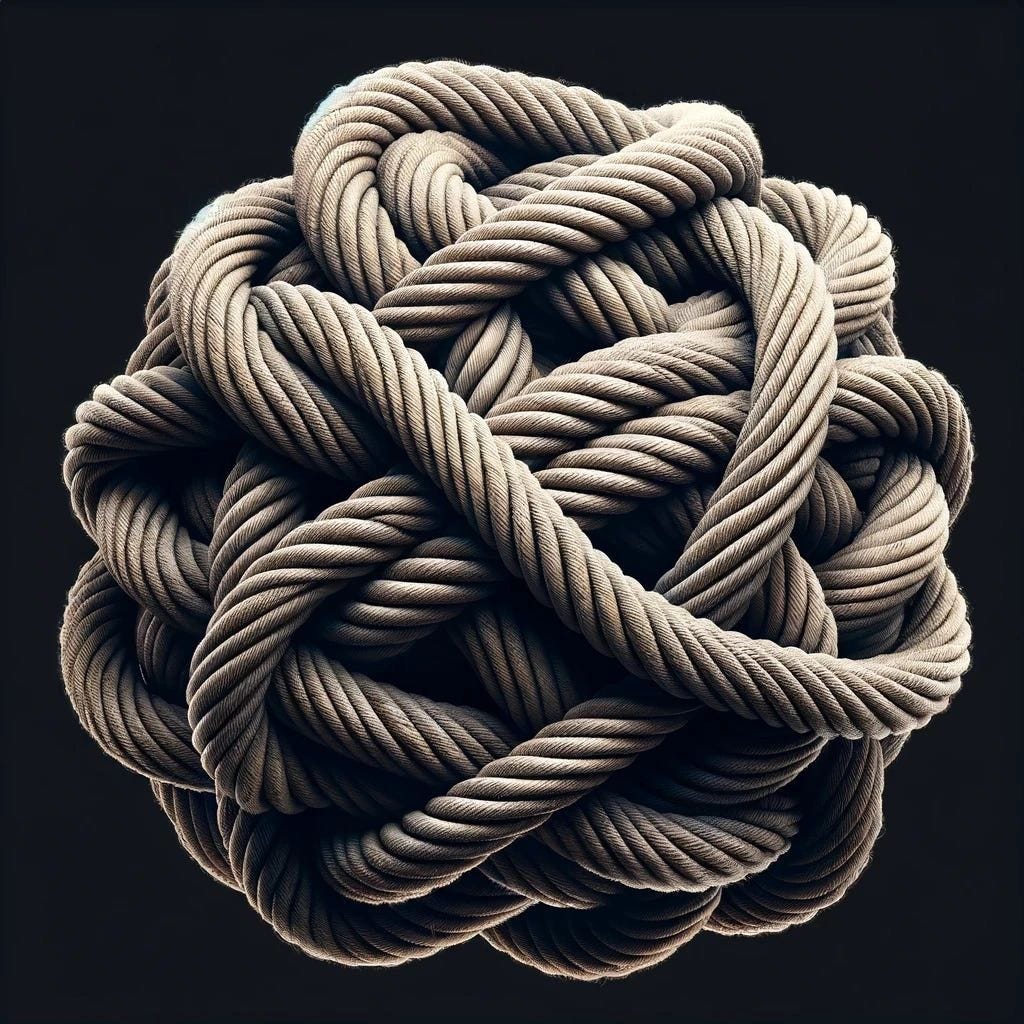

Ed. #77: The Gordian Regulatory Knot

CFPB is here to stay[1]

As most SCOTUS observers predicted[2], the CFPB’s funding source was found to not violate the Constitution’s Appropriation Clause. Coupled with the 2020 Selia Law case making the CFPB Director removable by the President at will, it seems clear that SCOTUS doesn’t think the CFPB is Constitutionally untenable as a whole.

Sometimes it’s hard to decipher how the SCOTUS justices arrive at their decisions, but the reasoning of these opinions[3] is less important[4] than the two high level takeaways for me: despite the appealing textual/originalist Federalist Society type arguments about the lack of clear Constitutional authority for any independent federal administrative agencies[5] (such as the CFPB, SEC, and FTC), (i) attacking the entire premise for such agencies on Constitutional grounds is not going to fly with these SCOTUS justices, and (ii) while we await the sinking of Chevron deference[6], it’s time to just get on with attacking individual agency actions instead of trying to shut the whole enterprise down in one case.[7]

Never go full Originalist

Also, this decision may serve as a bit of a note of caution to the 5th Circuit (and other courts) about extreme originalism in the face of historical events and progress. Alito’s dissent acknowledged that the Federal Reserve’s funding was ok because…., “it is a special arrangement sanctioned by history.”[8] “Sanctioned by history” might be a great name for a law school moot court or soccer team, but it’s not found in the US Constitution nor is the Fed. Clearly, that footnote and the rest of this case tells us that even the so-called conservative and/or Federalist Society justices (including the famously institutionally and consequentially unconcerned Gorsuch who joined Alito’s dissent) agree that, at least for some things, the Constitution must be read in context of the present. So, even Justice Gorsuch couldn't countenance the consequences of finding the Federal Reserve itself to be unconstitutional. Never go full Constitutional Originalist (or full libertarian: see footnote 9 of this link).

MBA Secondary Conference chatter

Meanwhile, Rob Chrisman has been known to ask the question (or, allegedly, overhear it at the MBA Secondary Conference in New York last week), “Rather than more regulations, how about better or more relevant regulations?” Well, the premise behind that question (whoever is asking it) makes me bristle. That is because the question seems to assume that if we only had better regulations and/or regulators that the mortgage market would be just great. Any truly faithful reader of this blog[9], however, would likely be able tell you that kind of assumption might set me off.

AI doesn't solve the knowledge problem

That hope for the promise of regulatory oversight flies in the face of F. A. Hayek’s knowledge problem as described in his essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society”. Hayek’s bottom line, which is a bedrock of my economic and political philosophy, is that there is no better mechanism than the market and prices to create more efficient outcomes for society. The problem with central planning is that it is impossible for planners (regulators) to have all of the real time information needed to rationally and efficiently distribute resources.

Now, someone might say that AI is a game changer on that equation. I don’t know about that. I asked Microsoft's AI to create a picture of four hands holding money and it gave me pictures with 7 and 5 hands. When I responded that there were more than 4 hands, it responded by stating unequivocally that there were just four hands in its creation. AI then created the picture I used on Musings #75 too. A good friend pointed out that one of the hands has 5 fingers (no thumb). So, no, I’m not ready to concede my political and economic philosophy to an arrogantly incorrect and creepy technology that can’t even count fingers and hands just yet. I'll admit, however, it writes well, even if it can't count.

Fair, transparent, and competitive junk fees

Anyway, while some regulation (like ATR) is necessary to prevent abuses,[10] asking for better regulation is a fool’s errand. Entrenched and politically motivated[11] bureaucracies (like those governing the mortgage industry) have no incentive to get rid of regulations even in the name of enhanced competition[12] and “improvement” only results in more complexity (think TRID’s improvement over the binding GFE, servicing regulation updates, or HMDA’s ever increasing data gathering requirements). So, the industry spent billions spent on TRID only to find out that now CFPB thinks everything disclosed in the TRID disclosures is a “junk fee”.

A better question for consumer protection regulation would be to ask whether the regulations we have now accomplish their purpose and whether the purpose is even worthy. RESPA was passed 50 years ago on the premise that referral fees increase costs to consumers. With all of the changes to technology and the marketplace that have occurred and continue to occur is that still empirically true? CFPB calls itself, “a 21st century agency that implements and enforces Federal consumer financial law and ensures that markets for consumer financial products are fair, transparent, and competitive.” Is anyone at CFPB going to look at whether that RESPA promotes a fair, transparent and competitive market,[13] or will they just keep tightening the knot on competition with incorrect and expansive RESPA interpretations like the February 2023 Advisory Opinion?

Broeksmit, Chopra, and regulatory knots

With all that as background, I took note of the comments made by MBA’s CEO Robert Broeksmit and CFPB Director Rohit Chopra at the MBA Secondary Conference. Broeksmit identified one of the most pernicious problems with the mortgage industry regulatory environment; a multiplicity of regulators and regulations that overlap and often are contradictory. As Broeksmit described these “regulatory knots”,

“[W]hen it comes to regulatory agencies, working together is increasingly difficult. I’m not just talking about differences of opinion and priorities, which certainly exist. I’m talking more about the bureaucracy’s enormous growth, which has created a dangerous system of confusing and contradictory mandates. Put simply, Washington, D.C. is tying us in ‘regulatory knots.’ As these knots grow tighter, they restrict our industry and the millions of people we serve.”… “What the CFPB calls ‘junk fees,’ federal agencies call ‘mandatory’… They pay for services like appraisals, credit reports, and flood certifications. Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Federal Housing Administration, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the USDA can’t guarantee a mortgage without these things, for good reason. They provide tangible benefits to borrowers and protect taxpayers. But now the CFPB is attacking them.”

Proving Broeksmit’s point, as reported by Housing Wire, Chopra’s speech at the MBA Conference railed against credit score and report fees, but seemed to suggest lenders are complicit in charging these fees,

“Lenders who attempt to pass on to borrowers the cost of screening applicants’ risk, do risk violating legal limitations on charging borrowers legitimate fees. This means as the cost of screening applicants rise, the cost increase for initial screening credit reports…some mortgage lenders will choose to evaluate fewer borrowers. The steep price increases raise a lot of questions for me. Why are lenders and borrowers being charged repeatedly for the same information?”

What about the GSEs and FHFA?

Broeksmit is totally correct that mortgage lenders are whipsawed by the requirements of consumer regulators and the secondary market investors who have been controlled by the government for over 15 years (some would say they now are the government[14]). If the ostensibly private, but quack like a duck public secondary market investors didn’t require lenders to obtain things like credit reports and scores from certain providers, lenders wouldn’t have to charge borrowers for those costs.

Sometimes there are good reasons for government to grant a monopoly (or oligopoly), but given changes in technology and the marketplace, it is time to reassess the economic value of the credit bureaus and credit score models that have been granted special privileges by the government for over 50 years. Chopra’s blaming the mortgage industry for those costs (even if only by suggesting complicity) is rightfully something for Broeksmit to shout about.

Meanwhile, as the federal regulator of Fannie and Freddie (if they aren't the government itself, then they are definitely an oligopoly), what’s the FHFA’s role here in doing something about these junk fees that Director Chopra is complaining about? Is Chopra also complaining to FHFA about credit report fees, appraisal fees and the like?

Be careful what you wish for

However…., Broeksmit’s proposed solution to untying the regulatory knot is to create a new “National Housing Policy Director.” An Alexander the Great coming to slice open this Gordian Knot if you will. Sorry, but I’m not in agreement with that. While I can imagine, as I am sure Broeksmit has, “the streamlined, collaborative, and commonsense leadership in the housing market” that the right person in such a position could achieve, I also have zero faith in either political party or government bureaucrats to turn over national housing policy to a single individual.

More importantly, I worry that such a person would have an agenda far different from whatever I might think makes good housing policy. To his credit, Broeksmit also recognized this risk, noting, “I fully understand that even with such a position, different presidents would continue to pursue different policies, some of which may be less than ideal. But that’s far preferable to the current system.”

I don’t see it as preferable because everything depends on who is appointed to the role. For example, as much as a deregulatory hawk like Mick Mulvaney might achieve al of the benefits Broeksmit hopes for in that role and then some, I don’t think anyone in the mortgage industry would be happy seeing equity focused corporate profit critic Elizabeth Warren (or 2-time disaster agency director Richard Cordray) get a chance to serve as National Housing Policy Director under a different party’s President.

Besides, in the absence of coherent housing policy generally and until a political party or Presidential candidate develops and wins elections with housing policy mandate, dueling bureaucrats is probably the best market oriented result we can hope for. Ironically, as noted in a Housing Wire interview last week, acting HUD secretary Adrianne Todman said, “we’ve not had a housing strategy for this country,“ which is essential since the housing market has been 'a roller coaster'. The responsibility for this should be on the departments 'with housing in their names,' she added." [emphasis added]. Ok. When you figure that strategy out Ms. Todman, please let us know. In the meantime, I'll be speaking later in June at the MBA of Hawaii's annual conference, suitably titled Pandamonium: Mastering the Mortgage Roller Coaster.

[2] I would include myself in that group: https://mortgagemusings.com/f/ed-68-kong-lives-cfpb-swats-away-the-funding-challenge

[3]Majority, Concurring and Dissenting opinions alike.

[4]And massively more boring unless you are really into British history and debates about the pre-Constitutional powers of the Parliament vs. the Crown. Suffice it to say, that only 2 out the 9 Justices felt that the CFPB’s funding went too far in terms of giving the executive branch the authority to fund its own initiatives. The rest of what they wrote about was seriously old school legal/historical reasoning to justify coming down on one side or the other of the issue.

[5] This has been a question since the New Deal. The Constitutional argument against independent agencies is not wrong in my view (show me where the Constitution says you can delegate executive authority to an independent agency), but the ship has sailed on reversing this Constitutional outlier entirely.

[6] I’m just a blogging hack, but I’ll be covering the demise of Chevron deference with two actual experts on administrative law; Troutman partner, Misha Tseytlin and Covington partner, Andrew Smith on Friday, May 31 at the 2024 Spring Consumer Financial Services Conference put on by the Conference on Consumer Finance Law. The CCFL is run by a fantastic governing committee of lawyers, but two lawyers deserve special shout out. McGlinchey partner (and avid Mortgage Musings footnote reader), Jim Milano, and Husch Blackwell partner, Sabrina Neff(Sabrina’s assistant Shellee deserves accolades too!) are the best. Unfortunately, the conference is sold out, so I can’t really encourage you to attend unless you already signed up.

[7]Likewise, notwithstanding amplification by one of the nation’s consumer law giants, I suspect the arguments suggested in a Wall Street Journal Op-Ed by Harvard Law Professor Emeritus Hal Scott are similarly likely to fail should the funding question be reproposed.

[8] See footnote 16 of the Alito dissent. Justice Thomas, writing for the majority, perhaps was the biggest surprise of all to those who think SCOTUS justices line up 6-3 conservative to liberal based on the party in control when they were appointed. Rather, Thomas concluded, “Although there may be other constitutional checks on Congress’ authority to create and fund an administrative agency, specifying the source and purpose is all the control the Appropriations Clause requires.”

[9] Like Jim Milano or perhaps even some of my friends at the CFPB?

[10] ATR is just a hard-coded consumer protection UDAAP rule, but I still think the industry is protected from its own excesses as well on that.

[11] CFPB used to refer to itself as “data driven”. I don’t see that in their statements anymore. Hmmm.

[12] “Now is the time on Shprockets” when I ask Director Chopra and my friends at the CFPB to tell me what in the world the LO Compensation Rule accomplishes today and why they haven’t simply gotten rid of this anti-competitive, cost raising, consumer unfriendly regulation, or at least made some clear interpretations that would benefit consumers to enable price competition. Hey, sometimes in regulations, like businesses, you make mistakes, and you need to change course. Isn’t correcting mistakes what “a 21st century agency that implements and enforces Federal consumer financial law and ensures that markets for consumer financial products are fair, transparent, and competitive” should do?

[13]It is unclear to me whether empirical data from the 1970s real estate market was obtained in reaching the conclusion that referral fees increase costs or whether it was just anecdotally true (which I am sure it was).

[14] Some common shareholders of the two GSE giants are no doubt secretly hoping that a new President will recap and release the GSEs and turn their worthless common stock into something valuable. I haven’t made up my mind yet on whether recap and release is a good idea for the GSEs and mortgage finance generally, but I can say for sure that it would be totally unfair to every bank shareholder wiped out by an FDIC takeover (like me) if Fannie and Freddie common stockholders are treated better after the government’s bailout when the GSEs were insolvent. To be sure, however, similar arguments could be made by shareholders of failed banks ineligible for TARP funds who could have survived with additional government support.